This article originally appeared in Outpost: The Traveller’s Journal. All words and pictures are copyright © Andrew Ross and may not be reproduced or copied in any manner without express written permission.

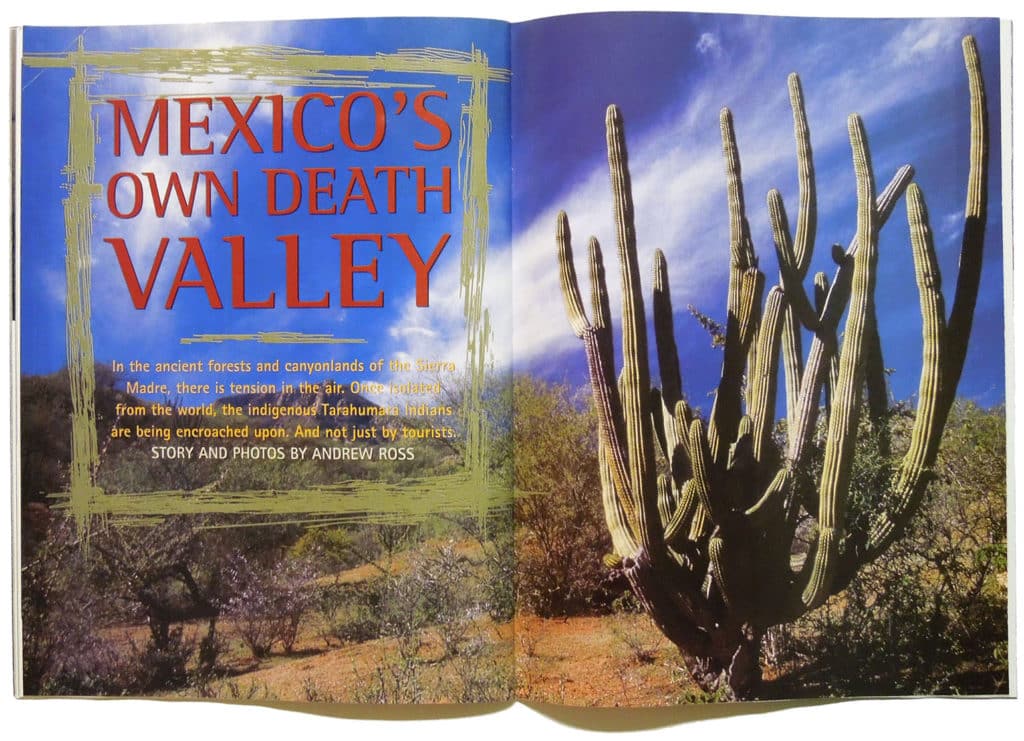

Mexico’s Own Death Valley

~ by Andrew Ross

In the ancient forests and canyon lands of the Sierra Madre, there is tension in the air. Once isolated from the world, the indigenous Tarahumara Indians are being encroached upon. And not just by tourists.

A sad tale of betrayal and a broken heart unfolds through the melody of a Mexican ballad. The music resounds warmly off the wooden walls of the small house, while the lingering smell of tortillas and beans mixes with smoke in the fireplace and floats up the chimney into the cold, clear sky of the Sierra Madre. Next to the stone hearth sits Isidrio, a stocky, indigenous man from the canyon lands of the Sierra. He is young and tall, with broad shoulders, huge, weathered farmer’s hands and a stern, emotionless face. His intimidating stature, torn jeans and dirty jacket project a rough appearance, yet his large fingers dance lightly across the fret board of his guitar and his gentle, melancholy voice gradually betrays the tough exterior and reveals a man who lives in a place of sorrow.

A sad tale of betrayal and a broken heart unfolds through the melody of a Mexican ballad. The music resounds warmly off the wooden walls of the small house, while the lingering smell of tortillas and beans mixes with smoke in the fireplace and floats up the chimney into the cold, clear sky of the Sierra Madre. Next to the stone hearth sits Isidrio, a stocky, indigenous man from the canyon lands of the Sierra. He is young and tall, with broad shoulders, huge, weathered farmer’s hands and a stern, emotionless face. His intimidating stature, torn jeans and dirty jacket project a rough appearance, yet his large fingers dance lightly across the fret board of his guitar and his gentle, melancholy voice gradually betrays the tough exterior and reveals a man who lives in a place of sorrow.

Isidrio comes from a remote indigenous community where a few dozen families farm corn and raise goats in the rugged terrain of the Sierra Madre Occidental. The Sierra, a mountain range on Mexico’s west coast, stretches 1,900 kilometres from the Arizona-New Mexico border into the Mexican state of Jalisco. In the northern region lies a sub-range of mountains called the Sierra Tarahumara, a rugged, inhospitable land of high plateaus and steep canyons that is named after the Tarahumara Indians who have lived there for more than 2,000 years. It is also the most biologically diverse ecosystem in North America and contains some of the largest stands of old-growth pine forests in Mexico. The isolation of the Sierra has protected the indigenous peoples and their lands from outsiders for centuries. They have survived conquering Spaniards and proselytizing missionaries, but in the last few decades they have faced new threats, perhaps even more violent and destructive.

Loggers and drug traffickers have invaded the remote canyons and ancient forests of the highlands. Once the loggers build roads into Indian lands and clear-cut the trees, los narcos – the traffickers – move in, plant opium poppies or marijuana and coerce the Indians into cultivating and harvesting the crops. Through violence and intimidation, they have turned this remote corner of Mexico, less than 200 miles from the U.S. border, into one of the most productive drug growing regions on earth. If the Indians resist or object, they are simply killed. Since the late 1980s, in Isidrio’s village alone, more than 40 traditional leaders and elders who stood up to the narcos have been murdered. His father is among the dead.

Loggers and drug traffickers have invaded the remote canyons and ancient forests of the highlands. Once the loggers build roads into Indian lands and clear-cut the trees, los narcos – the traffickers – move in, plant opium poppies or marijuana and coerce the Indians into cultivating and harvesting the crops. Through violence and intimidation, they have turned this remote corner of Mexico, less than 200 miles from the U.S. border, into one of the most productive drug growing regions on earth. If the Indians resist or object, they are simply killed. Since the late 1980s, in Isidrio’s village alone, more than 40 traditional leaders and elders who stood up to the narcos have been murdered. His father is among the dead.

All over the Sierra, people tell similar tales of sorrow. Several of them have come to the house in the mountains where Isidrio sat playing his guitar to attend human rights workshops. The house is owned by Edwin Bustillos, a gentle, soft-spoken agricultural engineer who bears permanent scars and spinal damage from several assassination attempts. He has been beaten and left for dead, his house shot up by automatic weapons, and his truck forced off a 100-metre cliff.

Bustillos was born in the Sierra and is the founder and director of a Mexican organization called CASMAC (Consejo Asesor de la Sierra Madre, A.C., translated it means the Advisory Council of the Sierra Madre). He has teamed up with Randall Gingrich, an American who wrote his master’s thesis on deforestation in the Sierra, to form the Sierra Madre Alliance for Human Rights and the Environment.

At the request of 15 indigenous communities, the two men have begun work to establish a biosphere reserve that would see more than 100,000 hectares of traditional lands protected. The indigenous communities would form the core of the reserves, which would be connected by corridors protecting the migratory paths of endangered species like the jaguar, Mexican grey wolf and thick-billed parrot.

“We came here to work on community-based forestry and preservation, but ended up fighting for human rights,” says Gingrich. “The government thinks we’re troublemakers. And I guess we are, because we don’t like seeing our friends get killed.”

~

Sitting outside the train station at Divisadero, thumbing through the pages of my guidebook, I come to a map of the Barranca del Cobre, the Copper Canyon, with a grey-shaded area marking Copper Canyon National Park. The sound of brakes on steel wheels distracts me and I look up to see the world famous Copper Canyon train pulling into the station. It shines like no other train in Mexico and is only for those who can afford to travel in first-class luxury.

Hundreds of tourists pile off and huddle at the edge of the canyon to gaze, point and roll videotape at one of the most amazing vistas in the Americas. Fifty million years before they arrived here, intense volcanic eruptions thrust expansive plateaus upward to elevations of more than 2,000 metres. Tectonic plates shifted and Baja California was ripped away from the mainland. As rivers flowed to the newly formed Gulf of Mexico, tearing chasms through the soft volcanic rock, numerous faults erupted and split the land into one of the largest labyrinths of canyons in the world – many deeper than the Grand Canyon.

Hundreds of tourists pile off and huddle at the edge of the canyon to gaze, point and roll videotape at one of the most amazing vistas in the Americas. Fifty million years before they arrived here, intense volcanic eruptions thrust expansive plateaus upward to elevations of more than 2,000 metres. Tectonic plates shifted and Baja California was ripped away from the mainland. As rivers flowed to the newly formed Gulf of Mexico, tearing chasms through the soft volcanic rock, numerous faults erupted and split the land into one of the largest labyrinths of canyons in the world – many deeper than the Grand Canyon.

The crowd from the train stands gazing over a chain link fence, oblivious to the fact that what they are looking at doesn’t really exist. Of course the stunning vista of canyons, rivers, and the Indians selling handicrafts are all very real, but what about the preserved wilderness of the Copper Canyon National Park that is in every traveller’s guidebook? That, unfortunately, is a figment of some map-maker’s imagination.

National parks are supposed to include areas that are off-limits to loggers, farmers and others who would destroy or exploit the land. The reality here is very different. “There’s been a park on the map for a long time,” says Randall Gingrich, “but it’s nothing. A lot of parks in Mexico and Latin America are just paper parks. Within the whole Copper Canyon there is not one core conservation area of biological significance!”

The group of tourists spends a few more minutes gazing out into the canyon, then files back onto the train to settle into their air-conditioned cabins and comfortable seats. I can’t afford the ride, so I walk to the road and wait in the heat for a second-class bus. Like most buses in Mexico this one has no muffler, so I hear it before I see it. As I climb on board, I pass the plastic Virgin Mary glued firmly to the dashboard and glance up to see a picture of Jesus taped to the ceiling above the driver. The brown vinyl seats of the retired school bus are packed with Tarahumaras and Mestizos (people of mixed Indian and European ancestry) and I have to stand as the bus mirrors the route of the train on its way to the town of Creel, 50 kilometres northeast.

The road we’re rumbling down is relatively new, but the train route was completed 30 years ago. With the completion of the 655-kilometre railway, the arid interior of northwestern Mexico was joined to the ports of the Pacific, bringing an end to the Tarahumara’s isolation in the Sierra.

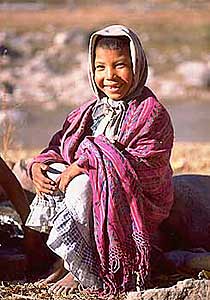

In the mid-1600s, Spanish Conquistadors, unable to conquer the Tarahumara, forced many of them to work in the silver mines. Periodic rebellions occurred throughout the Sierra, culminating in a wide-scale uprising in 1696. Violent reprisals by the Spanish left thousands dead and the severed heads of more than 60 Tarahumara men posted along the roadside. The rebellion was crushed and the Tarahumara silently withdrew into the remote canyons and highland forests. Today, their resistance continues, and many prefer to live and farm in the most rugged, inhospitable terrain rather than integrate into Mexican culture.

In the mid-1600s, Spanish Conquistadors, unable to conquer the Tarahumara, forced many of them to work in the silver mines. Periodic rebellions occurred throughout the Sierra, culminating in a wide-scale uprising in 1696. Violent reprisals by the Spanish left thousands dead and the severed heads of more than 60 Tarahumara men posted along the roadside. The rebellion was crushed and the Tarahumara silently withdrew into the remote canyons and highland forests. Today, their resistance continues, and many prefer to live and farm in the most rugged, inhospitable terrain rather than integrate into Mexican culture.

By fleeing to the highlands, the Tarahumara were able to avoid the Spanish, but the Jesuit missionaries, hungry for Indian souls, pursued them into the mountains. The missionaries remained a powerful force in the region until the King of Spain recalled them in 1767. The seeds of Catholicism were planted among the Indians, but after the removal of the missionaries, the Tarahumara were left relatively alone by both the government and the church for close to a hundred years.

During this period, the Tarahumara developed a unique belief system – a mixture of Catholic and indigenous traditions – that is most evident during the festival of Semana Santa. The Tarahumara believe that God and the Devil drink together and the Devil tries to harm God while he’s drunk. To protect God, men and women march around a church and pound goatskin drums continuously for three days. The sound, which echoes through the canyons, is meant to keep God awake in his inebriated state and is also said to represent the pounding of nails into Christ’s body. At the culmination of the festival, a straw effigy of Judas, with a huge wooden penis sticking out of his pants symbolizing spring fertility, is paraded around the village square. As the sun begins to set behind the mountains of the Sierra, Judas is tied to a stake and executed with bows and arrows. Then the transgressor’s straw body is torn to pieces, placed in a pile and set on fire for his betrayal of Christ.

The isolation that led to such unique Tarahumara rituals ended with the completion of the railway, which allowed outsiders to pour into the Sierra, and resources to pour out. Secluded forests became accessible to loggers and the Tarahumara were forced to withdraw even further into the mountains. The area around the railway, now known as the Copper Canyon and visited by thousands of tourists each year, was the first to be logged. Today the region is densely populated by ranchers, loggers, miners, hotels, trailer parks, and Indians who come to the area to look for work or to sell crafts to the tourists.

The isolation that led to such unique Tarahumara rituals ended with the completion of the railway, which allowed outsiders to pour into the Sierra, and resources to pour out. Secluded forests became accessible to loggers and the Tarahumara were forced to withdraw even further into the mountains. The area around the railway, now known as the Copper Canyon and visited by thousands of tourists each year, was the first to be logged. Today the region is densely populated by ranchers, loggers, miners, hotels, trailer parks, and Indians who come to the area to look for work or to sell crafts to the tourists.

Around the tourist centre of Creel, the forests have been razed four times over the last century. Before reaching Chihuahua City, the Copper Canyon train passes the bubbling sewage lagoons and billowing smokestacks of a massive pulp mill in Anáhuac. The mill underwent $350 million (US) worth of expansion and renovation recently. To help pay for the loan, thousands of hectares of pine forests (mostly plantations) that lie within the so-called Copper Canyon National Park will be turned into toilet paper for the North American market.

~

The train I saw in Divisadero beat our bus to Creel and when I arrive, the crowds have already taken to the dusty streets in search of pictures and handicrafts. I am on my way to meet with Edwin Bustillos and Randall Gingrich, so I jump on another bus and head south to Guachochi. Four hours and 30 pesos later, I arrive at the Estrella Blanca (White Star) bus station on the outskirts of town. Guachochi is near the edge of the Barranca Sinforosa, the deepest, most isolated canyon in the Sierra, which is said to be one of the major drug centres in the region. Only 100 kilometres from Creel, it couldn’t be farther from the five-star hotels and orchestrated encounters with Indians.

The gravel streets are littered with trash and lined with squat cinder block houses with tin roofs, steel doors and bars on the windows. The bright colours typical of walls and doorways throughout Mexico are nowhere to be seen. Grey is the only colour in Guachochi and everything is coated in a layer of dust. If there are drug traffickers here, the only place they’re spending their money is at the truck dealer. Considering the downtrodden, economically depressed appearance of Guachochi, there are an inordinate number of shiny pickup trucks with fat tires and tinted windows. Each truck slows as it passes me, an outsider, and I cautiously glance sideways into the black windows.

It was near here that Edwin Bustillos was pulled out of his car by five men, severely beaten and left for dead. Bustillos claims two of the men were off-duty police officers and that the attack was ordered by the municipal president of Guachochi, who has been linked to the drug cartel run by Artemio Fontes in Chihuahua City. While I’m thinking about all this, three olive-green helicopter gunships fly over the town and I realize this is one place I don’t want to be when the sun goes down.

While waiting for a taxi to take me to the Bustillos’s farm, I buy a Coke from a store selling Tarahumara crafts. The owner is curious about me and asks, “Que buscas aqui?” What are you looking for here? “I’m here to visit some friends,” I say.

“Te gusta la mota?” Do you like marijuana, he asks.

“Te gusta la mota?” Do you like marijuana, he asks.

“No, no that’s not for me,” I reply, trying to laugh off the suggestion.

“Te gusta la heroina?” Do you like heroin? I’m not sure if he is trying to make a sale or just playing with me, but I laugh again and say, “No.”

When I arrive at the farm, Bustillos’s father, Mautel, tells me that Edwin and Randall will arrive in a few days and that I am welcome to stay. Covered with partially-built log houses, rows of compost bins and plots of various ground covers and grasses, the farm has been set up as an agro-ecology training centre, where members of indigenous communities can come and learn about human rights and culturally-adapted techniques for gardening, composting, forestry management and watershed restoration.

That night, over a dinner of tortillas and beans, I ask him about the helicopters I saw in Guachochi. He says they come from a place called Baborigame on the other side of the canyon. I ask him what it’s like in Baborigame and he replies with two words: “Muchas pistolas.” Many guns.

A few days later, Edwin and Randall arrive with a film crew from Los Angeles that is producing a documentary about their work in the Sierra. Randall promised to take me to visit some of the last old- growth forests in the Sierra and I’m eager to find out where we are going. “Tomorrow we’re flying to Baborigame,” he says.

Baborigame is about 40 kilometres due south of Guachochi and there are three ways to get there: a two-and-a-half day walk, a 14-hour drive, or a 15-minute flight. I would have preferred the hike through the Sinforosa Canyon, but the rest of the group doesn’t have the time. So at sunrise the next morning, six of us squeeze into a five-seater plane. Our overweight pilot seems confident we can make it, but he checks the gas level to be sure.

With the passengers squeezed shoulder to shoulder, the pilot fires up the engine and within minutes, the ground beneath us tumbles over a precipice and falls 1,800 metres into the depths of the Sinforosa Canyon. We seem to be flying dangerously low, but I try to relax and enjoy the spectacular view, sure that my breakfast will soon make an appearance. Fifteen long minutes later, we’re on the other side of the canyon.

If there is a place in Mexico that can make Guachochi look appealing, this is it. A frontier town in every sense of the word, Baborigame surpasses any place in the Sierra with its reputation for lawlessness and violence. In the centre of town is an army fort built of roughly-cut logs and timber, complete with gun turrets facing in four directions. The municipal president, Manuel Rubio, is a convicted drug trafficker who won the election through fraud and intimidation of the indigenous majority. Even the local priest was removed after it was revealed that he was using the bishop’s plane to smuggle drugs out of, and arms into, the Sierra.

After putting our bags into the dingy rooms of the only hotel in town, we begin hiking into the deforested hills to visit a Tepehuan Indian community where members of CASMAC are conducting a workshop on indigenous education. When we arrive, we meet Alejandro and Francisco. They are supposed to be leading the workshop, but no one has shown up. Alejandro is a Tepehuan who works for the government translating Spanish textbooks into Tepehuan. He tells us that a local rancher, a woman named Trinidad, has been terrorizing the Indians and anyone who works with them. She accused Alejandro’s brother, a community leader, of raping an eight-year-old girl. Based on her accusations alone, he was arrested and put in jail without a trial. His brother was shot in the leg and Alejandro was robbed of 2,800 pesos ($420 US) while the police searched his house. Alejandro blames Trinidad and says her pistoleros, gunmen, recently killed five people in one day and have put an end to all gatherings and festivals.

After putting our bags into the dingy rooms of the only hotel in town, we begin hiking into the deforested hills to visit a Tepehuan Indian community where members of CASMAC are conducting a workshop on indigenous education. When we arrive, we meet Alejandro and Francisco. They are supposed to be leading the workshop, but no one has shown up. Alejandro is a Tepehuan who works for the government translating Spanish textbooks into Tepehuan. He tells us that a local rancher, a woman named Trinidad, has been terrorizing the Indians and anyone who works with them. She accused Alejandro’s brother, a community leader, of raping an eight-year-old girl. Based on her accusations alone, he was arrested and put in jail without a trial. His brother was shot in the leg and Alejandro was robbed of 2,800 pesos ($420 US) while the police searched his house. Alejandro blames Trinidad and says her pistoleros, gunmen, recently killed five people in one day and have put an end to all gatherings and festivals.

The next morning, Alejandro and Francisco, undaunted by Trinidad’s threats, are departing for another community and invite me along. Our destination is at the “end of the world,” says Francisco – a community called Soledad Vieja, Old Loneliness, which lies far away at the very edge of the canyon. We take Alejandro’s pickup and begin the slow drive up the bumpy logging road into the mountains. The road was built by logging companies who gained permission from the people of Soledad Vieja by telling them the road would go over the mountains and through the Sinforosa Canyon to Guachochi. The people thought this would be a good thing, but when the loggers reached the prime timber areas they stopped.

As we drive higher into the mountains, the pines grow larger and the forest becomes denser. This is a land of incredible bio-diversity where more than 23 different species of pine and more than 200 species of oak co-exist with tropical hydrangea vines and desert cactus. Less than three per cent of the original old-growth forests remain in the Sierra. Some of the last stands are in the mountains around Soledad Vieja, and are disappearing daily.

When we arrive, the leaders begin to tell us how Manuel Rubio, the municipal president of Baborigame, coerced them into a corrupt agreement for logging rights to their land. He offered each of the 30 families in the community 1,000 pesos ($160 US) a year for the right to cut their trees. They accepted and Rubio demanded their land deeds to complete the contract. They had no idea how much a tree was worth, but when they saw trucks loaded with timber leaving their land each day, they began to suspect they weren’t being treated fairly. When they asked for more money, Rubio said they had given him their deeds and he was now owner of the land. Nothing was ever signed or written down.

In addition to extortion by loggers, the people of Soledad Vieja live in fear of the narcos. Three people were murdered recently when they surprised a group of traffickers bringing a shipment up out of the canyon. After a day of listening to these stories, I ask Francisco what their next step will be. He matter-of-factly replies, “We will consult a lawyer, conduct an investigation and then try to stop the contract with Rubio.” This seems like an impossible way to deal with people like Rubio and his bosses in the drug cartels, but Francisco assures me they have had some success.

In 1990, a logging company built a road into nearby Pino Gordo without gaining permission from community leaders, and then tried to charge them $100,000 US or the equivalent in trees. The community first took up arms to chase the loggers out, but with the help and advice of CASMAC, they took the logging company to court instead. A judge ruled that they didn’t have to pay for the road and the residents of Pino Gordo declared their community a conservation area. The declaration was notarized and the illegal logging stopped.

I made it back to the Bustillos’s farm outside Guachochi in time to attend the CASMAC workshop for indigenous leaders from around the Sierra. In an effort to educate the community leaders about government negotiations and double-talk, the organizers dress in cowboy hats and carry rifles to a mock practice meeting to discuss the Indians’ concerns about land usage.

I made it back to the Bustillos’s farm outside Guachochi in time to attend the CASMAC workshop for indigenous leaders from around the Sierra. In an effort to educate the community leaders about government negotiations and double-talk, the organizers dress in cowboy hats and carry rifles to a mock practice meeting to discuss the Indians’ concerns about land usage.

In a polite and dignified manner, the indigenous leaders present their concerns about drug trafficking, logging and general disrespect for their lands and way of life. The government representatives respond as expected, with patronizing words about their concern for the communities’ problems. But in the end, they use words about laws, legal contracts and the prosperity of the nation to diminish and denigrate the concerns of the indigenous people.

As the meeting continues, a logging truck on its way out of the canyon drives past the farm and belches black smoke into the air.

The dark cloud lingers over the farm as a grim reminder of the enormous tasks facing this community as they strive to transform this place of sorrow into a place of hope.